You Won’t Believe What Reykjavik’s Urban Spaces Are Hiding

Reykjavik isn’t just a launchpad for waterfalls and glaciers—its urban core pulses with quiet creativity. Tucked between colorful houses and quiet streets are unexpected public spaces where art, nature, and daily life blend seamlessly. I walked for hours, discovering how this compact city uses design, light, and community to turn ordinary corners into moments you remember. It’s not about landmarks—it’s about feeling the rhythm of a place that values simplicity and soul. The city doesn’t shout; it hums. And if you listen closely, you begin to understand how urban living can be both functional and deeply human. Reykjavik teaches us that beauty doesn’t need grand gestures—it thrives in thoughtful details, in the way light reflects off a puddle near a bus stop, or how a bench is placed just right to catch the morning sun. This is a city shaped not by spectacle, but by care.

The Quiet Power of Small-Scale Design

Reykjavik’s charm is not found in towering skyscrapers or sprawling boulevards, but in its deliberate embrace of human-scale urbanism. The city’s planners have long understood that comfort in public spaces begins with proportion. Buildings rarely rise beyond three or four stories, allowing the skyline to remain soft against the surrounding mountains and sea. This low-rise character ensures that pedestrians never feel dwarfed or disoriented, fostering a sense of intimacy even in the city center. Wide sidewalks, gently curved streets, and the absence of heavy traffic contribute to an atmosphere where walking feels natural, not like a chore. Unlike larger capitals that prioritize speed and efficiency, Reykjavik moves at a pace that invites observation, conversation, and pause.

One of the most telling examples of this philosophy is Laugavegur, the city’s main shopping and cultural artery. While bustling with cafés, boutiques, and galleries, the street retains a residential warmth. Benches are spaced thoughtfully, allowing people to rest without disrupting foot traffic. Crosswalks are frequent and clearly marked, making it easy for families, older adults, and children to navigate safely. The consistent building height creates a visual rhythm, while setbacks and small front gardens give each structure its own identity without breaking the street’s harmony. There are no glass towers interrupting views or casting long shadows—just a continuous, breathable streetscape that feels welcoming at any hour.

Public squares in Reykjavik serve not as grand ceremonial spaces, but as quiet punctuation marks in the urban fabric. Austurvöllur, adjacent to the Alþingi (Iceland’s parliament), is a prime example. During the day, it hosts chess players, dog walkers, and students reading between classes. In winter, it becomes a gathering point for seasonal markets and outdoor events. The square’s design is simple—open grassy areas, scattered trees, and a few sculptural elements—but its success lies in its accessibility and versatility. It doesn’t try to be everything; instead, it offers space for whatever the moment requires. This restraint is a hallmark of Reykjavik’s approach: urban planning that listens more than it declares.

Even the materials used in public infrastructure reflect this sensitivity. Sidewalks are often paved with textured stone or concrete, providing grip during icy months while adding visual interest underfoot. Streetlights are low and warm-toned, illuminating pathways without overwhelming the night sky. The city’s commitment to walkability extends beyond aesthetics—it’s embedded in policy. Car use is discouraged in the center, with ample bike lanes and public transit options reducing congestion. The result is a city where movement feels safe, quiet, and unhurried. In a world increasingly dominated by urban sprawl and noise, Reykjavik stands as a reminder that less can be more when it comes to designing spaces where people truly want to be.

Color as Urban Identity

One of the first things visitors notice about Reykjavik is its palette. Houses painted in soft mint green, buttery yellow, and deep ocean blue line the streets, their corrugated metal roofs catching the light in surprising ways. These colors are not random expressions of whimsy—they are part of a deeper urban language that shapes navigation, identity, and continuity. Each neighborhood carries its own tonal signature, helping residents and visitors alike orient themselves without relying solely on street signs. In Vesturbær, for instance, a cluster of red-roofed homes marks the heart of the district, while Hlíðar’s pastel-toned facades create a gentler, more residential feel. Color, in this city, functions as both wayfinding tool and cultural marker.

The origins of this colorful tradition are practical as much as aesthetic. In the early 20th century, imported corrugated steel sheets—available in pre-painted red, green, and blue—became a popular roofing material due to their durability and ease of installation. Over time, homeowners began painting the walls to match, creating a harmonious effect that quickly became iconic. What began as a solution to material constraints evolved into a defining feature of Icelandic urban design. Today, city planners protect this visual heritage through guidelines that encourage color coordination without enforcing uniformity. New developments are expected to complement, not clash with, the existing palette, ensuring that the city’s character remains intact even as it grows.

What makes Reykjavik’s use of color particularly effective is its resistance to commercialization. Unlike some European cities where bright facades are reduced to photo backdrops for tourists, Reykjavik’s color scheme remains rooted in daily life. You won’t find neighborhoods repainted solely for Instagram appeal, nor are there themed zones designed to attract visitors. The colors belong to the people who live there, chosen for personal taste within a shared understanding of balance. A yellow house next to a gray one might have a blue door—small variations that reflect individuality while maintaining cohesion. This balance between personal expression and collective harmony is central to the city’s identity.

Walking through Reykjavik’s residential areas, one begins to see how color influences mood and perception. On overcast days, the bright roofs lift the spirit, breaking the monotony of gray skies. In summer, when daylight lasts nearly 24 hours, the hues glow with an almost surreal intensity. Even in winter, when snow blankets the ground, the colors remain visible, offering visual warmth in a season defined by cold. The city doesn’t hide its infrastructure—utility boxes, bus stops, and traffic signals—are often painted in complementary tones, turning functional elements into subtle design features. This attention to detail signals a deep respect for the urban environment, one where beauty is not an afterthought, but a necessity.

Public Art That Feels Personal

Art in Reykjavik does not reside behind glass or within museum walls—it lives on sidewalks, tucked into alleyways, and perched on rocky outcrops along the harbor. Unlike cities where public art is monumental or didactic, Reykjavik favors intimacy. A mosaic of ceramic fish scales embedded in a crosswalk, a wooden carving of a seated figure in a quiet park, or a poem etched into a metal plaque beside a bench—these are the kinds of encounters that define the city’s artistic spirit. They don’t demand attention; they reward curiosity. This decentralized, human-scaled approach ensures that art is not a luxury, but a shared experience woven into the rhythm of everyday life.

One of the most beloved installations is the “Sun Voyager” (Sólfar), a stainless steel sculpture by Jón Gunnar Árnason located along the seaside path. Resembling a Viking ship set sail toward the horizon, it faces Mount Esja across the bay, creating a powerful visual dialogue between art, nature, and history. Though it draws photographers and tourists, locals also claim it as their own—a place to pause, reflect, or watch the sunset. The sculpture’s placement on a public walkway ensures it remains accessible at all hours, free from barriers or admission fees. It stands not as a monument to be admired from a distance, but as an invitation to linger.

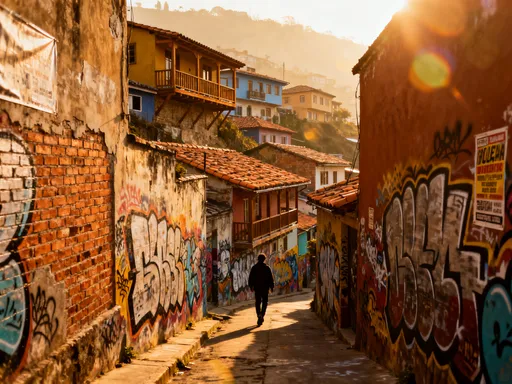

Beyond the well-known pieces, Reykjavik thrives on hidden art. Murals appear unexpectedly behind cafés in the old harbor district, their vibrant colors contrasting with weathered brick walls. Some are commissioned through city programs, while others emerge spontaneously, supported by a culture that values creative expression. In certain zones, artists are allowed to paint without permits, as long as their work remains non-commercial and respectful of the neighborhood. This trust fosters a dynamic, ever-changing streetscape where art feels alive, not curated. It also empowers local voices, ensuring that the city’s visual identity reflects its residents, not just outside artists or corporate sponsors.

The city’s support for grassroots creativity extends to small-scale interventions. Tile projects, where residents and schools create ceramic artworks for public paths, have become a tradition in some neighborhoods. These mosaics often depict local wildlife, folklore, or seasonal changes, grounding art in community memory. Even utility spaces—storm drains, retaining walls, and underpasses—are reimagined as canvases for color and storytelling. This democratization of public space sends a powerful message: that beauty belongs to everyone, and that creativity is not the domain of experts alone. In Reykjavik, art is not something you go to see—it’s something you stumble upon, a quiet surprise in an ordinary moment.

Green Spaces as Urban Breathers

Despite its compact size, Reykjavik is a city deeply intertwined with nature. Green spaces are not afterthoughts or decorative add-ons—they are essential components of urban life. From the central Tjörnin Pond to the expansive Botanical Garden, these areas serve multiple roles: ecological, recreational, and social. They provide habitat for birds, manage stormwater runoff, and offer residents a place to reconnect with the natural world without leaving the city. More than that, they function as communal living rooms—places where people gather not for events, but for the simple acts of feeding ducks, walking dogs, or sitting in silence with a book.

Tjörnin, a small lake in the heart of downtown, exemplifies this integration. Surrounded by government buildings, museums, and cafes, it remains a wild sanctuary for migratory birds, including swans, ducks, and Arctic terns. In winter, when the surface freezes, locals skate across its smooth ice, while in summer, children toss breadcrumbs from the stone-lined banks. The pond is carefully maintained—fenced only where necessary, with native plants encouraged along the edges. Its presence transforms the surrounding area into a calmer, more reflective zone, where the pace of life slows even amidst the city’s busiest district.

The Reykjavik Botanical Garden, part of the larger Laugardalur Valley park system, offers a different kind of retreat. Home to over 5,000 plant species, including many native Icelandic varieties, it serves as both a research site and a public sanctuary. Pathways wind through themed sections—rock gardens, medicinal herbs, and Arctic flora—inviting exploration and education. Unlike formal European gardens, this space feels open and unstructured, encouraging visitors to wander freely. Families picnic on grassy slopes, students sketch plants, and elderly couples walk hand in hand along shaded trails. The garden’s accessibility—open year-round and free of charge—ensures that it remains a true public resource, not a privilege for a few.

Even smaller interventions contribute to the city’s green ethos. Planters filled with hardy perennials line sidewalks, and green roofs are increasingly common on new buildings, helping to insulate homes and support pollinators. Rain gardens—depressions planted with water-tolerant vegetation—manage stormwater naturally, reducing strain on the drainage system while adding pockets of green. These features are not hidden; they are visible, celebrated parts of the urban landscape. They signal a commitment to sustainability that doesn’t sacrifice beauty or usability. In Reykjavik, nature is not something preserved in reserves far from the city—it is invited in, given space to thrive, and treated as an equal partner in urban design.

Light and Darkness: Designing for Extremes

Reykjavik exists at the edge of the Arctic Circle, where daylight shifts dramatically between seasons. In winter, the sun barely rises, casting the city into nearly 18 hours of darkness. In summer, it never fully sets, bathing streets in a soft, golden glow well past midnight. These extremes could make urban life feel oppressive or disorienting, but Reykjavik has learned to work with, not against, the light. The city’s lighting design is not merely functional—it is emotional, aiming to preserve well-being, safety, and a sense of wonder during the long nights.

Streetlights in Reykjavik are carefully calibrated to emit a warm, amber hue, mimicking the color of candlelight or sunset. This choice is intentional: cooler, bluer light can disrupt circadian rhythms and worsen seasonal affective disorder, a concern in regions with prolonged darkness. By using warmer tones, the city creates a more comforting atmosphere, making evenings feel safer and more inviting. Illuminated pathways guide pedestrians through parks and along the harbor, their gentle glow encouraging movement even in the coldest months. Building façades are often lit from below, highlighting architectural details and adding depth to the nightscape without contributing to light pollution.

Seasonal events further transform the city’s relationship with darkness. The Reykjavik Light Festival, held annually in early February, turns the urban environment into a canvas of creativity. Temporary installations—glowing arches, interactive light sculptures, and projected art on building walls—bring color and joy to what might otherwise feel like the bleakest time of year. Residents stroll through illuminated parks, children play with fiber-optic wands, and cafés host candlelit readings. The festival doesn’t fight the dark; it celebrates it, reminding people that beauty can emerge from stillness and shadow. It’s a communal act of resilience, a way of saying that even in the longest night, there is warmth and connection.

Light also plays a role in daily rituals. Many homes and workplaces use daylight-mimicking lamps during winter months to support mental health. Public buildings often feature large windows to maximize natural light when it’s available, and interior spaces are painted in light-reflective colors. Even playgrounds are designed with visibility in mind, ensuring that children can be seen clearly even in low light. These small, thoughtful choices accumulate into a city that feels considerate of its inhabitants’ needs. Reykjavik doesn’t try to erase the challenges of its climate—it adapts to them with intelligence and care, proving that urban design can be both practical and poetic.

Community Hubs Over Tourist Traps

While Hallgrímskirkja and Harpa Concert Hall draw international visitors, the soul of Reykjavik lives in quieter, more intimate spaces. These are the places where locals gather not to pose for photos, but to live. Sólfar Café, nestled near the harbor and steps from the Sun Voyager sculpture, is one such spot. With its large windows facing the water, it attracts early risers with coffee and fresh pastries, fishermen on break, and parents with strollers. There are no menus in five languages, no souvenir shelves—just simple food, warm service, and a view that changes with the tides. It’s a place shaped by routine, not spectacle.

Even more central to daily life are the city’s public swimming pools. Sundhöllin, Reykjavik’s oldest geothermal pool, is more than a place to swim—it’s a social institution. Families come after school, older adults meet for conversation in the hot tubs, and friends unwind after work. The ritual of showering before entering the water, a cultural norm in Iceland, reinforces a shared sense of respect and cleanliness. The architecture itself—simple, functional, with an emphasis on natural materials—complements the experience. Steam rises from the pools into the cold air, creating a dreamlike atmosphere, especially at dusk. These pools are affordable, accessible, and open year-round, making them true democratic spaces where all ages and backgrounds mix naturally.

Other neighborhood hubs include local libraries, community centers, and shared gardens. The Reykjavik City Library, with its quiet reading rooms and children’s storytelling hours, functions as a cultural anchor. Some districts have “house of neighbors” spaces—small buildings where residents can borrow tools, attend workshops, or simply chat over coffee. These low-key venues foster connection without fanfare, building social fabric one conversation at a time. They are not designed for viral photos or influencer content; they exist for the quiet, cumulative power of belonging.

What unites these spaces is authenticity. They are not staged for outsiders, nor do they rely on novelty to attract people. Instead, they thrive on consistency, accessibility, and a deep understanding of local needs. In a world where many cities reshape neighborhoods to cater to tourists, Reykjavik protects its community spaces with quiet determination. They are not hidden—they are simply unmarked by hype. To find them, you must slow down, observe, and be willing to participate in the rhythm of daily life. And when you do, you begin to see that the heart of a city isn’t in its landmarks, but in the spaces where people simply are.

Lessons from a Compact Capital

Reykjavik offers a powerful counter-narrative to the idea that great urban design requires scale, wealth, or dramatic architecture. Instead, it demonstrates that impact comes from intentionality. By prioritizing pedestrians, embracing climatic challenges, and trusting local input, the city has created an environment where life feels both comfortable and meaningful. Its success lies not in any single policy or project, but in a consistent philosophy: that cities should serve people, not vehicles, corporations, or tourists. This human-centered approach has made Reykjavik one of the most livable small capitals in the world—a place where safety, beauty, and community coexist without pretense.

Other cities can learn from Reykjavik’s restraint. In an era of urban expansion and digital distraction, the city reminds us that small gestures matter. A well-placed bench, a warm streetlight, a patch of wildflowers in a planter—these details shape how we feel in public spaces. Reykjavik proves that sustainability is not just about technology or infrastructure, but about culture. When residents feel ownership over their environment, they care for it. When art is accessible, it enriches daily life. When nature is integrated, it heals.

For travelers, the lesson is equally important. To truly know Reykjavik, you must move slowly. Skip the guided bus tour. Put away the checklist of must-see sights. Instead, walk without a destination. Sit by Tjörnin and watch the swans. Visit a neighborhood pool. Order coffee at a corner café and linger. Let the city reveal itself in quiet moments—the way sunlight hits a red roof, the sound of laughter from a playground, the smell of geothermal steam in the air. These are the experiences that stay with you, not because they are dramatic, but because they are real.

Reykjavik does not hide its wonders behind gates or price tags. They are in the streets, in the light, in the way people move through their days with purpose and peace. It is a city that understands the value of stillness, of simplicity, of belonging. And in that understanding, it offers a blueprint for urban life that is not just efficient, but humane. As more cities grapple with congestion, isolation, and climate change, Reykjavik stands as a quiet example of what is possible when design begins with care.