Lost in the Stone Labyrinth: Damascus Like You’ve Never Seen It

Walking through Damascus feels like flipping through pages of an ancient book—each alley a sentence, each stone a word. The city’s terrain isn’t just hills and valleys; it’s layers of time carved into the earth. I wandered without maps, letting the rhythm of narrow passages and sun-baked courtyards guide me. What makes this place truly special isn’t just history—it’s how the land itself tells the story. You’ve never felt a city like this. Damascus does not present itself all at once. It reveals itself slowly, step by step, in the way sunlight filters through latticework, in the sound of water beneath ancient flagstones, in the subtle rise and fall beneath your feet. This is a city shaped not by blueprints, but by centuries of life adapting to the natural world. To walk its streets is to engage in a quiet dialogue with geography, history, and human resilience.

The First Step: Entering Damascus’ Living Terrain

Damascus is not a city imposed upon the land; it is one that has grown from it, like vegetation finding purchase in stone. Nestled at the edge of the Barada River and cradled by the foothills of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, the city’s elevation shifts gently but persistently. These changes are not dramatic—no sudden cliffs or plunging ravines—but they are constant, like a slow breath rising and falling beneath the surface of daily life. As you step into the old quarter, the ground begins to rise almost imperceptibly, guiding your path like an invisible hand. Unlike grid-planned metropolises designed for efficiency, Damascus evolved organically, shaped by necessity, climate, and topography. The streets follow the natural contours of the land, curving around high points, descending into shaded hollows, and climbing again toward sunlit terraces. This organic flow gives the city a rhythm, a pulse that can only be felt on foot.

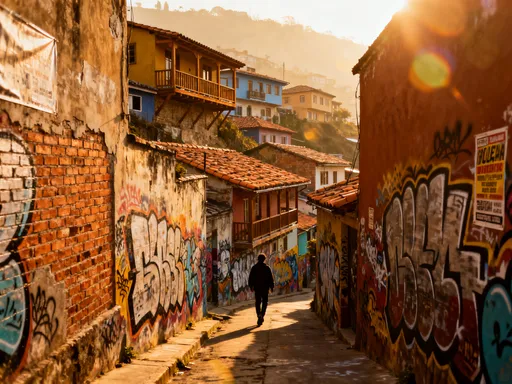

The experience of walking through Damascus is fundamentally different from navigating modern urban environments. There are no long, straight boulevards stretching into the distance. Instead, the city unfolds in fragments—glimpses of courtyards, sudden drops into narrow alleys, staircases that appear without warning. Each turn offers a new vantage point, a fresh alignment with the surrounding landscape. A minaret that seemed distant moments ago now rises just above the rooftops. A patch of sky framed by ancient stone suddenly opens into a small plaza bathed in golden light. This layered perception is not accidental; it is the direct result of building with, rather than against, the terrain. The elevation changes prevent monotony, ensuring that no two blocks feel the same. Even seasoned travelers accustomed to historic cities often remark on the physical sensation of moving through Damascus—not merely observing it, but participating in its form.

What sets Damascus apart is how seamlessly human life integrates with its physical setting. Houses are not simply placed on hillsides; they are terraced into them, their rooftops becoming pathways, their courtyards carved into the slope. Water channels follow natural drainage lines, and wind patterns influence the orientation of doorways and arcades. This deep harmony between architecture and geography did not emerge overnight. It is the product of thousands of years of observation, adaptation, and incremental refinement. The city’s builders did not seek to dominate nature—they learned to listen to it. And today, anyone who walks its streets can still hear that quiet conversation in the way the ground rises beneath their feet.

Wandering the Old City: Where Geography Meets History

The Old City of Damascus, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited urban centers on Earth. Its labyrinthine streets are not the product of haphazard development but of deliberate adaptation to both geography and human need. Here, the land and history are inseparable. The city’s layout reflects centuries of response to environmental conditions—water availability, defensive requirements, and microclimates—all shaped by the undulating terrain. Streets curve not for ornamentation, but because they follow ancient watercourses or provide strategic cover from wind and sun. The famous Suq al-Hamidiyah, stretching from Bab al-Hadid to the Umayyad Mosque, traces the path of a buried riverbed, its arched roof rising and falling with the natural slope of the land beneath. Walking through it, you feel the incline underfoot, a subtle reminder that even the grandest covered market in the city answers to the earth’s contours.

Underfoot, the materials shift with the terrain and function. In the higher, drier sections, smooth limestone slabs reflect the sun, creating bright, open corridors. In lower areas, where moisture collects, worn basalt flagstones provide better grip and durability. These transitions are not marked by signs or boundaries—they are felt, experienced with every step. Courtyards, the heart of traditional Damascene homes, are rarely on a single plane. They often descend in gentle steps or are built across multiple levels, connected by short staircases or sloping walkways. This tiered design allows for better air circulation, natural drainage, and visual privacy, all while accommodating the uneven ground. The architecture does not fight the land; it embraces its irregularities, turning them into features of beauty and utility.

One of the most striking aspects of the Old City is how its verticality shapes social life. Because space is limited and the ground is rarely flat, buildings rise in layered formations, with upper floors projecting over alleys or opening onto shared terraces. Windows are positioned to catch breezes or morning light, and doorways are often recessed into thick walls to provide shade. These design choices, born of necessity, create a richly textured urban fabric. Residents move through a three-dimensional network of paths, stairs, and rooftops, forming connections that are as much vertical as they are horizontal. This density of movement and interaction fosters a strong sense of community, where neighbors know each other not just by name, but by the rhythm of their daily comings and goings. The terrain, in this way, becomes a silent architect of social cohesion.

The Role of Water: How the Barada River Shapes the City

No discussion of Damascus’ terrain is complete without acknowledging the Barada River—the lifeblood that made urban settlement possible in this arid region. Flowing from the snowmelt of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, the Barada carries fresh water across the desert edge, splitting into a network of canals that have nourished the city for over three thousand years. These waterways are not merely functional; they are central to Damascus’ identity, shaping its development, economy, and daily rhythms. Even today, though much of the original system has been covered or altered, the presence of water remains palpable. In certain alleys, you can still hear the quiet rush beneath stone slabs. In courtyards, small fountains continue to trickle, their sound a constant companion to conversation and prayer.

The distribution of water in Damascus relies on a simple yet brilliant principle: gravity. The city’s gradual slope allows water to flow naturally from higher elevations to lower ones without the need for pumps or mechanical systems. Ancient engineers harnessed this drop, constructing a network of canals and underground channels known as qanats to deliver water to homes, mosques, and gardens. These channels were carefully aligned with the terrain, ensuring consistent flow while minimizing erosion and evaporation. In neighborhoods like Jaramana and Qanawat, remnants of these systems are still visible—stone-lined channels running alongside footpaths, small bridges marking crossings, and depressions in the earth indicating former irrigation routes. Though modern infrastructure has replaced much of the original network, the legacy of this hydraulic intelligence endures in the city’s layout and land use.

Water also influences movement and orientation. Paths often follow the course of buried streams, and bridges—some dating back to Roman times—mark key crossing points. The placement of markets, public baths, and religious sites was historically determined by proximity to water sources. Even the Umayyad Mosque, one of the most important Islamic landmarks in the world, is situated near the convergence of major channels, reflecting the sacred value placed on water in Islamic tradition. For visitors, following the flow of water—real or imagined—offers a powerful way to navigate the city. It provides a natural logic to what might otherwise seem like a chaotic maze. By aligning your journey with the river’s path, you move not just through space, but through layers of history and human ingenuity.

The Garden Belt: Green Terraces on the Edge of the Desert

East of the city center lies the Ghouta oasis—a green belt of terraced gardens that has long served as Damascus’ agricultural and spiritual refuge. Once spanning over 40,000 hectares, this fertile crescent was made possible by the Barada’s overflow and a sophisticated network of underground channels that brought water to elevated plots. Though urban expansion has significantly reduced its size, fragments of Ghouta remain, offering a glimpse into a way of life that harmonized cultivation with topography. The gardens are not flat expanses but stepped terraces, built to manage runoff, conserve moisture, and maximize shade. Citrus, fig, and olive trees grow in layered formations, their roots gripping the soil of gentle slopes, while grapevines climb trellises above narrow footpaths.

Walking through the remaining gardens of Ghouta is a sensory shift. The air cools noticeably, carrying the scent of jasmine, mint, and damp earth. The sound of traffic fades, replaced by birdsong and the rustle of leaves. Sunlight filters through dense canopies, casting dappled patterns on the ground. This microclimate is not accidental; it is the result of deliberate landscape engineering. The terraces slow down water flow, allowing it to seep into the soil rather than run off. Tall trees provide shade for understory crops, and the orientation of rows follows the sun’s path to optimize growth. These techniques, developed over generations, reflect a deep understanding of local conditions and a commitment to working with nature rather than against it.

For Damascenes, the gardens have always been more than a source of food. They are places of rest, reflection, and celebration. Families gather in orchards for picnics, children play among the trees, and elders sit in shaded pavilions sipping tea. The act of tending to the land is itself a form of continuity, linking present generations to ancestors who cultivated the same soil. Even as the city expands, efforts continue to preserve what remains of Ghouta, recognizing its value not just as green space, but as a living archive of sustainable land use. For visitors, a walk through these gardens offers a moment of stillness, a reminder that urban life need not be disconnected from nature. In Damascus, the boundary between city and countryside has never been rigid—it is porous, shifting, and deeply intertwined.

Modern Damascus: Terrain Adaptation in Contemporary Life

The relationship between land and life in Damascus extends far beyond the Old City. In modern districts like Ashrafieh, Malki, and Abu Rummaneh, the city’s topography continues to influence design and daily routines. Unlike many contemporary cities that flatten landscapes to accommodate uniform construction, Damascus retains its natural slopes, with buildings terraced into the hillsides. Roads wind gradually uphill, staircases connect street levels, and public spaces often take advantage of elevated viewpoints. This respect for terrain creates a built environment that feels cohesive and grounded, where new developments do not erase the past but extend its logic into the present.

In Ashrafieh, for example, residential buildings are arranged in stepped formations, with lower homes shaded by those above and rooftop terraces offering panoramic views of the city and distant mountains. Parking areas are often built into slopes, doubling as small amphitheaters for informal gatherings. Staircases between streets become social spaces—places where neighbors stop to talk, children play, and vendors sell fruit or tea. These adaptations are not merely aesthetic; they are practical responses to the land, reducing the need for extensive excavation or artificial support structures. They also promote walkability, encouraging residents to move through the city on foot, engaging with their surroundings in a more intimate way.

Even satellite neighborhoods on the city’s outskirts follow this principle, climbing the hillsides in gentle arcs that mirror ancient settlement patterns. This continuity—between old and new, natural and built—is one of Damascus’ defining characteristics. It speaks to a cultural value that prioritizes harmony over control, adaptation over domination. In a world where many cities prioritize speed, efficiency, and uniformity, Damascus offers an alternative vision: one where progress does not mean erasing the land’s memory, but learning to live within its rhythms. This is not a city that resists modernity; it reinterprets it through the lens of place.

Practical Wandering: How to Navigate the Terrain Like a Local

To truly experience Damascus, you must walk. No vehicle, no guided tour, no digital map can convey the subtle shifts in elevation, the play of light and shadow, the way the city reveals itself only to those who move slowly. Begin at Bab Sharqi, the ancient Eastern Gate, and allow yourself to drift westward, following the gentle incline toward the Umayyad Mosque. Wear comfortable, grippy shoes—the old stone surfaces can be slippery, especially after rain. The morning hours are ideal, when the air is cool and the sunlight slants through narrow alleys, illuminating courtyards and archways in golden hues. Avoid the midday heat by planning routes that pass through shaded souqs, covered walkways, or garden courtyards.

Carry water, even for short walks. The elevation changes, though subtle, increase physical exertion more than you might expect. A stroll that appears flat on a map can involve dozens of small ascents and descents, each contributing to fatigue if unprepared. Instead of relying solely on GPS, use natural landmarks to orient yourself. The minaret of the Umayyad Mosque is visible from many points in the city, serving as a reliable reference. Hilltop mosques, the distant ridge of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, and the flow of pedestrian traffic can all help you stay grounded. Most importantly, allow yourself to get lost. The maze-like structure of the Old City is not a flaw—it is the essence of the experience. Let the terrain guide you. Follow the sound of water, the scent of bread from a neighborhood oven, the sight of a shaded courtyard inviting rest.

Engage with residents when possible. Many are accustomed to curious visitors and may offer directions, share stories, or invite you to pause for tea. These moments of connection enrich the journey, transforming a simple walk into a meaningful encounter. Ask about favorite paths, hidden gardens, or family homes passed down through generations. You’ll often find that personal histories are deeply tied to specific places—streets climbed daily, courtyards where children played, rooftops with views of the mountains. In Damascus, memory is embedded in the land, and every conversation adds another layer to your understanding.

Why This Terrain Matters: A Living Legacy

The terrain of Damascus is not merely a backdrop to history—it is an active participant in it. Every slope, channel, terrace, and staircase reflects a long-standing relationship between people and place, a testament to sustainable living in a challenging environment. In an era of rapid urbanization, where cities are often built with little regard for natural landscapes, Damascus stands as a powerful example of organic urbanism. It shows that beauty, functionality, and resilience can emerge when human design listens to the land rather than overrides it.

This legacy is not frozen in time. It continues to evolve, shaping how people live, move, and connect today. The city does not announce its wisdom loudly; it reveals it quietly, in the way a staircase appears where it’s needed, in the coolness of a shaded alley, in the persistence of water flowing beneath ancient stones. To walk through Damascus is to become part of this ongoing story, to feel the weight of centuries underfoot and the quiet pulse of a city that has learned to breathe with the earth.

For the thoughtful traveler—especially one who values depth, authenticity, and connection—Damascus offers a rare gift. It invites you not just to see, but to feel. To slow down. To listen. In a world that often moves too fast, this city reminds us that some of the most profound experiences come not from grand spectacles, but from the simple act of walking with awareness, one step at a time, through a landscape that remembers everything.